Side-by-side images depict NASA’s Curiosity rover (illustration at left) and a moon buggy driven during the Apollo 16 mission. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Apollo 17 astronauts drove a moon buggy across the lunar surface in 1972, measuring gravity with a special instrument. There are no astronauts on Mars, but a group of clever researchers realized they havejust the tools for similar experiments with the Martian buggy they’re operating.

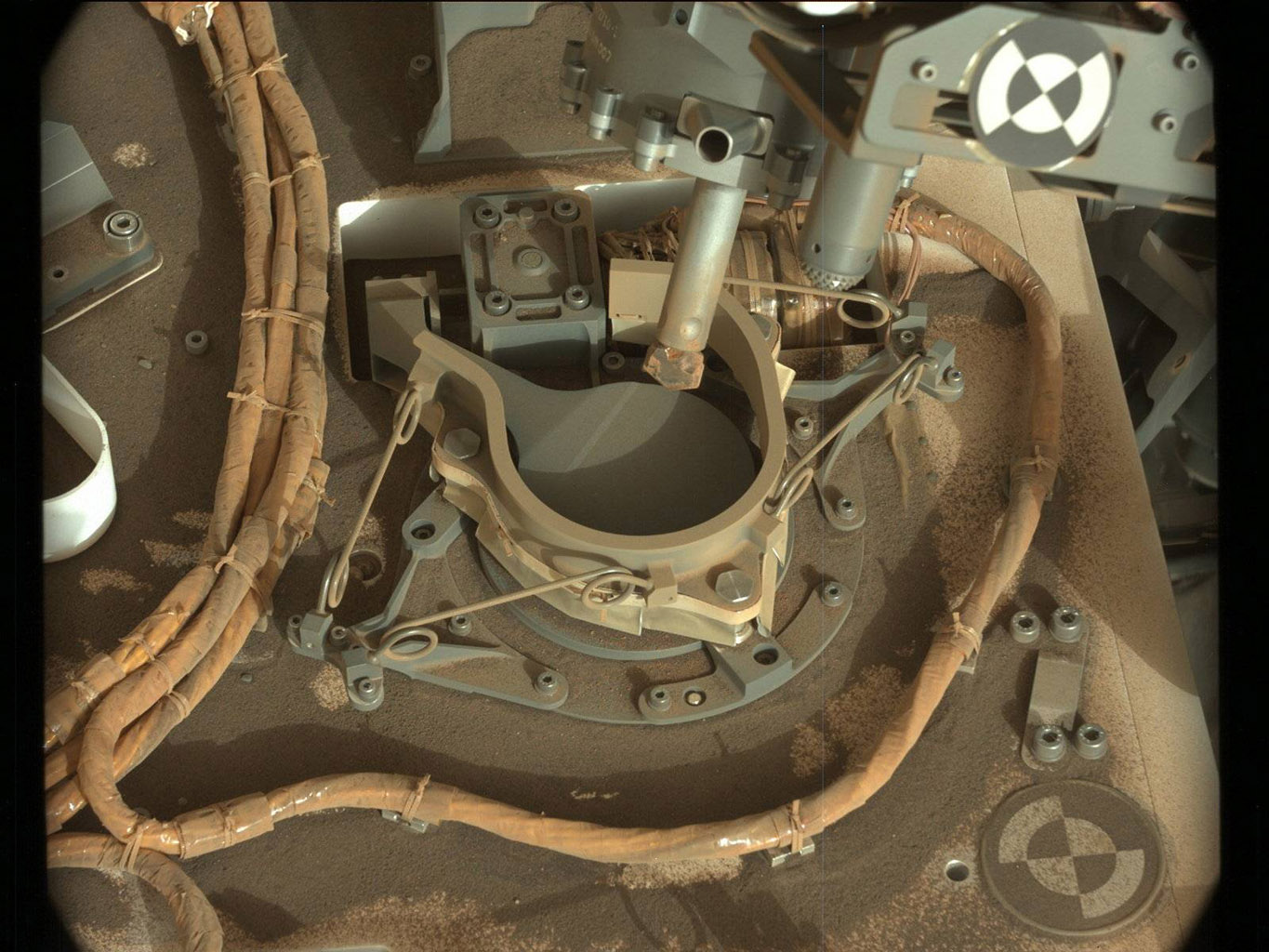

In a new paper in Science, the researchers detail how they repurposed sensors used to drive the Curiosity rover and turned them into gravimeters, which measure changes in gravitational pull. That enabled them to measure the subtle tug from rock layers on lower Mount Sharp, which rises 3 miles (5 kilometers) from the base of Gale Crater and which Curiosity has been climbing since 2014. The results? It turns out the density of those rock layers is much lower than expected.

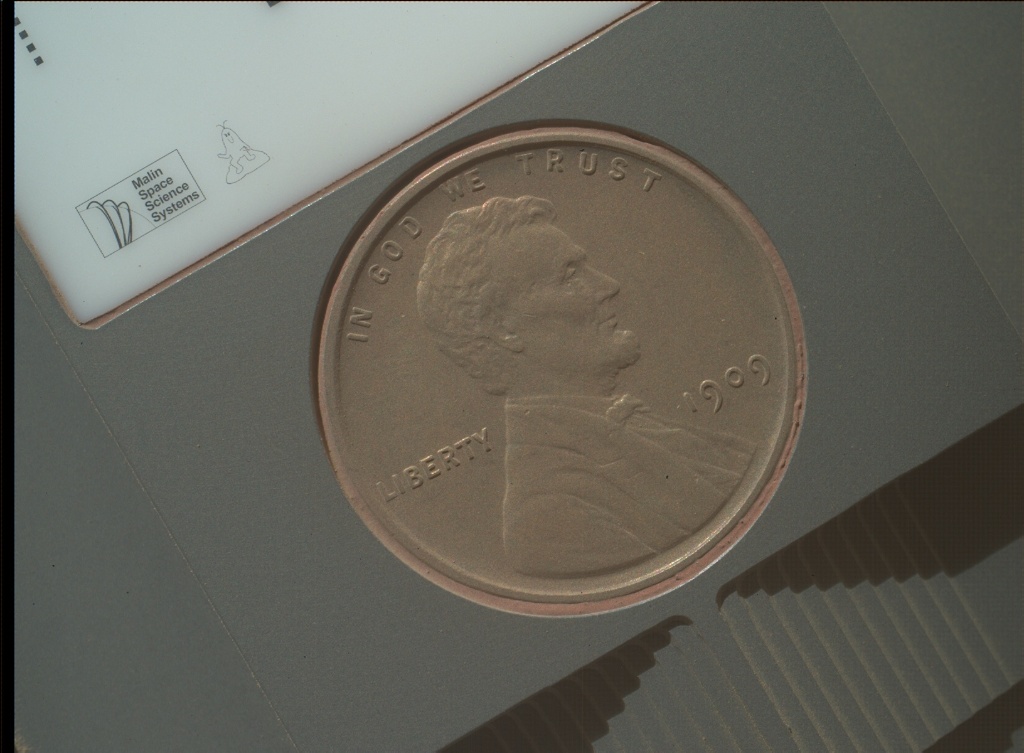

Just like a smartphone, Curiosity carries accelerometers and gyroscopes. Moving your smartphone allows these sensors to determine its location and which way it’s facing. Curiosity’s sensors do the same thing but with far more precision, playing a crucial role in navigating the Martian surface on each drive. Knowing the rover’s orientation also lets engineers accurately point its instruments and multidirectional, high-gain antenna.

By happy coincidence, the rover’s accelerometers can be used like Apollo 17’s gravimeter. The accelerometers detect the gravity of the planet whenever the rover stands still. Using engineering data from the first five years of the mission, the paper’s authors measured the gravitational tug of Mars on the rover. As Curiosity ascends Mount Sharp, the mountain adds additional gravity – but not as much as scientists expected.

“The lower levels of Mount Sharp are surprisingly porous,” said lead author Kevin Lewis of Johns Hopkins University. “We know the bottom layers of the mountain were buried over time. That compacts them, making them denser. But this finding suggests they weren’t buried by as much material as we thought.”